Community

Blue Dragon Rising

Blue Dragon Children’s Foundation has spent almost two decades working to help Vietnamese street kids, and rescue trafficked women

Published

6 years agoon

A guy poses as a john in a brothel in a Chinese border-town, eyeing up two young women who have been trafficked from Vietnam to work as sex slaves. To save the girls, he not only needs to convince the pimp he wants both girls, but that he we wants his way with them off the premises. Negotiations are frantic. He must not blow his cover. He is running on instinct. Minutes later, girls safely bundled into a car, he is speeding toward the Vietnamese border with the rescued girls, desperately hoping they will not be caught by the local thugs who just realized the last trick they sold was a very different trick to the one they had in mind.

It sounds like a movie, but it’s not. This is real life. It is the very first rescue of Vietnamese women trafficked to China, as executed in 2007 by the Blue Dragon Children’s Foundation, a mid-sized NGO focused on helping Vietnam’s “street kids” as well as rescuing women (and children) who have been trafficked for the purposes of prostitution, labor exploitation and forced marriage, often but not always to mainland China.

The founder and co-CEO of Blue Dragon, Michael Brosowski, tells Chào that things are a little different these days: the rescues not so dramatic. Over many years the foundation has honed its processes to make them as safe as possible, and they do not carry those same risks as they did back in the day.

“I thought if I had been born in Vietnam, this probably would have been me. I could have been on the street.”

“We go there, find them, then help them escape” he says, briefly sounding like a Liam Neeson character. “We don’t go kicking down the door or confronting people or anything like that. We just help them get out of the building they’re in, and we drive them away. Simple as that. Get them back to Vietnam.”

A dragon is born

Though a large portion of Blue Dragon’s work is spent preventing, and saving women from human trafficking, it didn’t start like that. In 2002 when Brosowski first came to live in Vietnam he noticed the many street kids: some homeless, some runaways, some working as shoe shine boys, some even working in the sex trade. Virtually all were not in school and living in some degree of poverty. Growing up poor in rural Australia, often living with his family in caravans, Brosowski saw something of himself in these children.

“I thought if I had been born in Vietnam, this probably would have been me. I could have been on the street,” he says. “I mean my family was poor but we were never hungry, and I thought this is something I can help with. At the beginning it was just a volunteer initiative.”

Blue Dragon grew fast. Such were the number of children on Vietnamese streets, the work never seemed to end. It still has not. Brosowski can almost pinpoint the exact moment when he realized the project was going to be much bigger than he imagined.

“I remember when we were thinking that this could be an organization for the long term. I was keeping some notes and files on the kids we helped,” he says. “There was one day [in 2003] when I pulled all the notes and files on the table, and there were 30 files. And I remember thinking this is probably the limit of the kids we can help. Thirty is a good number.”

From a folder of 30 children the foundation expanded, and the numbers are a little different now. Since it was founded, Blue Dragon says it has served over half a million meals, obtained legal papers for nearly 14,000 people, sent over 5,000 children back to school or education, rescued over 900 people from trafficking, built over 100 homes, reunited over 500 runaways with their families, and helped put scores of human traffickers and pedophiles behind bars. Right now they have 100 of their former children in university. They have even successfully helped oversee changes in the Vietnamese law to protect boys from pedophilia; a previous loophole meant that people could not be convicted for sexually molesting boys. The scope of the work is astounding. It does not take long to work out that what Blue Dragon does is remarkable, jaw-dropping even.

“Sometimes you just go to work and you just cry. Sometimes you just get angry, you just want to build a wall. Yeah, we see a lot of horrible things the whole time. It’s so dark. It’s hard to function.”

It is easy to ooh-and-ahh at good intentions. If more people went to the lengths that Brosowski and his team of 100-odd staff went to in order to help others, the world would undeniably be a better place. But it is the execution that is staggering. Being well-intentioned is an important part of the battle, but being well-intentioned and achieving real success are two entirely different things.

A holistic approach

With so many staff, a large multi-purpose office and youth center in Hanoi, several shelters, provincial offices, a gym and yoga room, a large dining hall to feed the children, occasional medical bills, school fees, a computer room and a vast support network, it is unsurprising that the costs in keeping Blue Dragon going are considerable. They are funded through a mixture of large donors, and smaller contributions of people who maybe pay only 10 or 20 dollars per month. Brosowski says the large donations are incredibly useful, but if they suddenly stop it can leave a big hole in their finances. It is therefore important to build up a base of lots of smaller donors so if a few of the larger ones stop, it does not hurt the foundation as much.

Much of Blue Dragon’s success comes from its holistic approach. There are charities that do fantastic grassroots work and focus on, say, feeding and clothing the homeless, and there are others that take a more structural approach by lobbying governments to change laws to improve human rights. Both approaches are worthwhile, but it is less common for a singular institution to tackle both ends and everything in between. Blue Dragon does exactly this.

The foundation is by turns a shelter, youth club, foster home and employment service. It keeps children clothed but it also helps them to get back to school or to reunite with their families. Blue Dragon employs a diverse staff, everyone one from social workers and lawyers to psychologists and cooks. It rescues women from forced marriages, but also sees that they get the support they need to re-enter society afterwards.

“In China the girls are locked up. Sometimes they have been there for one day and sometimes they have been there 20 odd years. “

The toughest battle

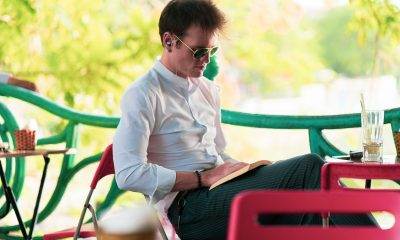

Despite their many successes, Blue Dragon staff are not starry-eyed about the work they do. They are keenly aware it is a constant battle. Do Duy Vi is the chief coordinator of the Blue Dragon street kid program. He believes that without the right support networks, the chances of the average street kid in Vietnam having positive outcomes in life is low.

“Almost impossible, actually,” he says. “There are just so many things that could go wrong. They are so vulnerable.” Vi is 32, though he looks younger. Despite his relaxed, easy going charm, it is clear the job carries a heavy emotional toll on him. Dealing with children that have been exposed to domestic abuse, drug overdoses and pedophilia is tough. It can take people to the brink.

“Sometimes you just go to work and you just cry. Sometimes you just get angry, you just want to build a wall. Yeah, we see a lot of horrible things the whole time. It’s so dark. It’s hard to function,” he says. “You wonder if you can do anything. You think, should we stop? We see children who got beaten up badly and are in the hospital. We see the children that go home only to be abandoned by their family members. It is not easy. Especially for the kids that you know, the kids that you care for.”

It is likely that these issues hit Vi a little harder than most. He used to be a street kid himself. Though he is now effectively in a senior management position, he used to be a “shoe shine boy” waking up to walk up to 12 hours a day across Hanoi’s streets in a desperate bid to make any money he could.

He met Brosowski while working on the streets in 2002, and was soon living in one of the foundation’s shelters near Long Bien in Hanoi. Vi soon took some classes in English and computing, and went on to work in hospitality for several years. He loved the industry but about 10 years ago decided to return to Blue Dragon and has worked there ever since.

“I just wanted to do something to give something back, to pay back actually. I was making good money and I had a good life, but I just wanted to do something. I didn’t mean to stay for 10 years,” he says. “I loved my job as a bar tender selling wines and cigars and I thought that would be my main job forever.”

“There was a drop-in center [at Blue Dragon] and they needed a supervisor to play with the kids and hang out with them. So I thought I would do that for six months. Michael used to go out on the street and talk to street kids. But at that time Michael was quite busy running the organization.

“There were not enough people to go finding kids on the street … So I told him maybe I can do that. I used to live on the streets. So, yeah, it’s easy for me to go out on the streets and talk to them and find them.”

“So they buy a baby without the woman, just the baby … The women are so poor, they see no ability to raise their own children. And traffickers offer them a very good payment, about 80 million VND for a baby.”

Human trafficking

Due to the foundation’s name and in part because they are two such very different issues, many people do not expect Blue Dragon Children’s Foundation to be so active dealing with human trafficking, which mostly focuses on young adult women. “That can be difficult to explain,” Brosowksi says. “Sometimes I just tell people, look, it is very common that the women we rescue have children of their own, so we are helping that way.”

The foundation’s work in trafficking comes, like so much of what they do, from a desire to help. Blue Dragon does not really do, turning people away. It is not in its DNA. So if it hears of a case of a woman in trouble, it sets about trying to help, usually through a mixture of investigative work, and liaising with border guards, as well as local authorities in China and Vietnam.

“In China the girls are locked up. Sometimes they have been there for one day and sometimes they have been there 20 odd years. The first opportunity they have to get a telephone, they call,” Brosowski says. “They call their mother who call the police, and they open a file and investigate. But they also might call us, as we might be able to support the family, or we might be able to help find their daughter more quickly.”

“If the girl has a phone we can communicate with her. She might have a phone but she might not know where she is. But we try to help. Can she describe where she is? Sometimes they might know the name of the city and that’s all. “

Le Thi Hong Luong, 29, is Blue Dragon’s anti-trafficking coordinator. Despite her young age, she has now worked at Blue Dragon for seven years and is likely one of the country’s foremost experts on human trafficking in Vietnam. She says that nobody really knows the true extent of the trafficking of women from Vietnam to China, explaining that good data is difficult to obtain, in part because many victims manage to independently return to Vietnam and never tell authorities what they have been through, due to the ordeal and the social stigma surrounding it.

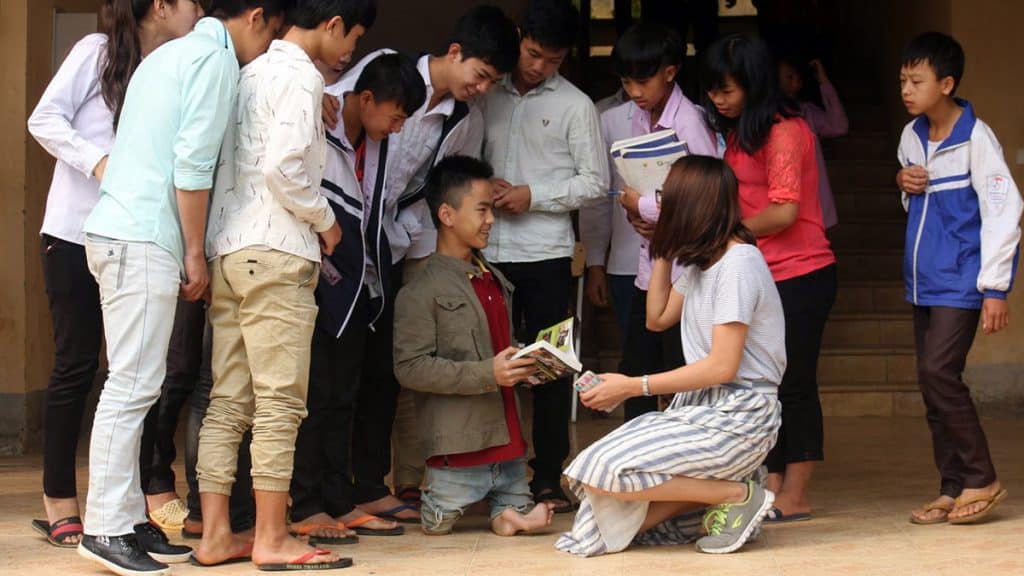

Sitting in the dining hall at Blue Dragon is quite the experience. Kids runs past, pushing and shoving, screaming and laughing, boisterous but happy.

“There’s many forms of trafficking. For sex trafficking, it includes sex workers and forced marriage. Forced marriage is quite common. Very common,” Luong says. “Now there’s also labor exploitation, organ removals, selling babies and other stuff. We work with all of these forms. Both domestically and in China.”

Luong says that a typical trafficker may prey on a potential victim from their own home by sending out large batches of friend requests on Facebook or other social media in the hope that a few vulnerable girls accept their requests.

”They chat together for a while and then after one month, two months, or even six months, he invites her on a date, to hangout or meet face to face. There’s lots of that,” she says. “This ‘boyfriend,’ will maybe offer to take her to visit his hometown, but actually take her on an illegal border crossing.”

Blue Dragon is making things more difficult for traffickers, but an end to human trafficking does not look in sight anytime soon. Traffickers quickly evolve and move into other areas, using new techniques and other shocking ways to make money. Child labor used to be very common, but is less so now, then forced marriages rose rapidly, and now the trading of babies, for example, seems to be on the rise.

“We have not rescued any [domestically trafficked] children in Vietnam for several years now, but sex trafficking into China keeps going. And the traffickers also have new methods. Recently they focus [on babies] because in China the men need a wife, but they also need children. [Holding] a woman is maybe sometimes quite annoying, as she can run away,” Luong says. “So they buy a baby without the woman, just the baby … The women are so poor, they see no ability to raise their own children. And traffickers offer them a very good payment, about 80 million VND for a baby.”

Since 2007, Blue Dragon has rescued about 900 victims from the sex, marriage and forced labor industry (400 from forced labor, and over 500 from forced marriages and the sex industry). The foundation continues to do all it can to stamp out what is one of the world’s worst crimes.

The boy in a cage

Morally the issue of trafficking women for forced marriage and prostitution is clear cut. “No one likes this,” Brosowski says. “You have to be the lowest of the low to make any money from this [trafficking].” But with street kids, horrific as it is, the situation may be less clear cut. There are families that allow their children to work because they are in deep poverty. Or parents that neglect their children through a lack of education or not knowing what to do. Blue Dragon tries not to judge.

Brosowski tells a story of a young boy who was effectively being kept prisoner by his parents. They thought he was being “a bit naughty so had locked him in a cage … The father had built this, well, kind of like a prison more than a cage, so half of the room was ceiling to floor bars, but they built a door, but it had been locked so long they couldn’t open it. He had this bucket for a toilet.”

“I don’t even know everyone’s name anymore,” he says, almost admonishing himself.

He says the parents were almost relieved when Blue Dragon arrived, and told him that they did not know what to do. “They told us they knew what they were doing was not right, and they knew that they could go to prison.”

The parents told Brosowski that every time the boy went out, he would not come home. He would hang out with “bad kids,” so they thought by locking him at home, they were helping.

“What a complex situation. That boy now lives with us with his parents’ blessing. They actually support him. They send him money every month as a way to show him they care about him, and we take him home every now and then for supervised visits,” Brosowski says. “Everything we do is never black and white, well rarely.”

The Blue Dragon Family

Sitting in the dining hall at Blue Dragon is quite the experience. Kids run past, pushing and shoving, screaming and laughing, boisterous but happy. They come and swap jokes with Brosowski in Vietnamese, and he asks them all how they are doing. He is like a favorite uncle that always makes the time to chat, except most people are not an uncle to 100 kids at a time. “I don’t even know everyone’s name anymore,” he says, almost admonishing himself.

Lunch at the foundation is Brosowski’s favorite time of the day, as it gives him time to unwind a little and hang out with the kids he has devoted most of his adult life to helping. It is here that you are struck by how Blue Dragon resembles something of a family, albeit a large and unruly one. The staff talk about “our kids” or “Blue Dragon kids,” perhaps not even realizing quite how paternal they sound. People stay in touch long after the foundation has helped them. “You don’t just leave!” Brosowski says. “Coming up to Tet, we will have a lot of the old kids coming back just to drop in.”

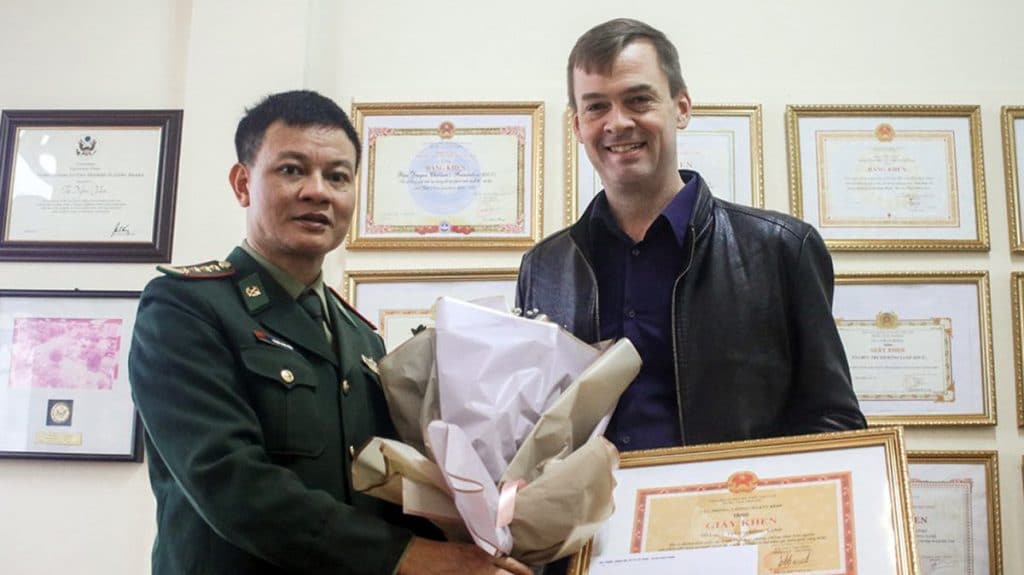

Its longevity and many successes mean that Blue Dragon comes under the spotlight more than most NGOs in Vietnam, and Brosowski as one might imagine has been widely recognized for his work. He was even made a member of the Order of Australia in 2012 to honor him for his work helping children.

Questioned about this he says the awards are nice, yet he doesn’t seem fully comfortable with them. “I find them ethically challenging, because the awards are very often for me. If my staff all walked out the door I couldn’t do a thing. I have never even been to China,” he says. “I just take the credit, right. So they are a little bit uncomfortable. ”

Brosowski’s modesty makes sense. Blue Dragon is not around to get pats on the back or pick up baubles, but to help end human trafficking and give the children on Vietnam’s streets a better chance in life, and they are succeeding.

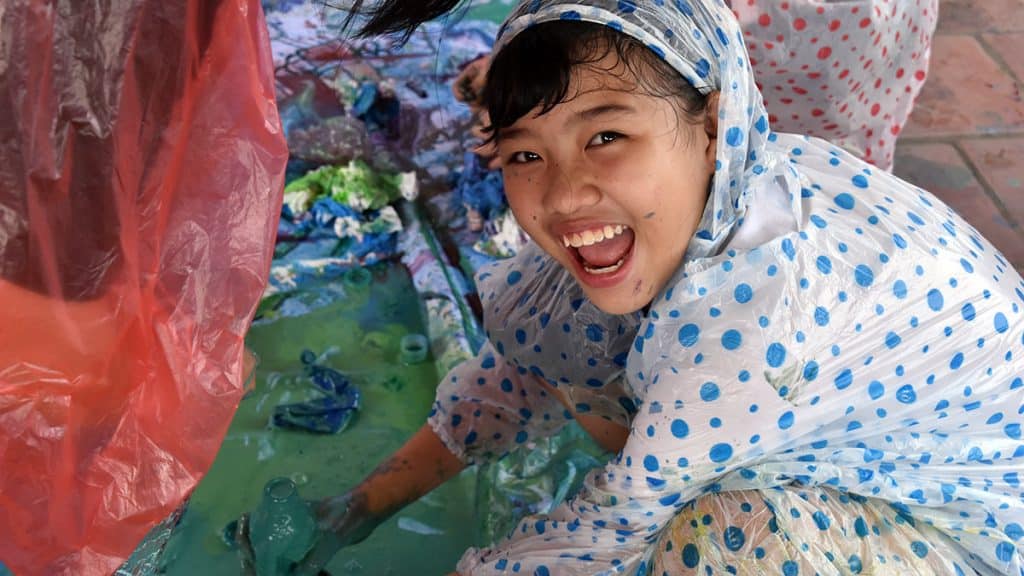

Whether it is housing a child far from home, helping a kid to learn karate, acrobatics or to sing, or simply letting these kids from the wrong sides of the tracks know that there are people around that love them, what Blue Dragon does really works–from the bottom right through to the very top.

It is an organization that really does show that humanity has a chance of making a better world for itself and its future.

If you would like to support or become involved in the Blue Dragon Children’s Foundation, visit their website https://www.bluedragon.org/ to see how you can help.

You may like

-

SpamCham returns to Hanoi for first 2026 meetup

-

Hanoi community group working to make city safer

-

Vietnam issues new rules on foreign work permits

-

Vietnam to introduce microchipped ID cards

-

Vietnam closes cross-dressing pimp’s prostitution operation

-

Vietnam labels ‘Viet Dynasty’ as terrorist organization seeking to overthrow government

-

Tax from online advertising in Vietnam reaches 1 trillion VND