Community

Coronavirus is fueling racism and it needs to stop

Covid-19 is being used to fan the flames of racism throughout the world

Published

6 years agoon

In the age of coronavirus, it seems the prejudice and racism the disease inspires often seems as potent as the virus itself. The outbreak has led to racist incidents throughout the world, ranging from childish mockery of foreign cultures right to verbal and physical assault. These cowardly attacks are not only unnecessarily cruel but threaten to further divide humanity, perhaps even long-after social distancing is over.

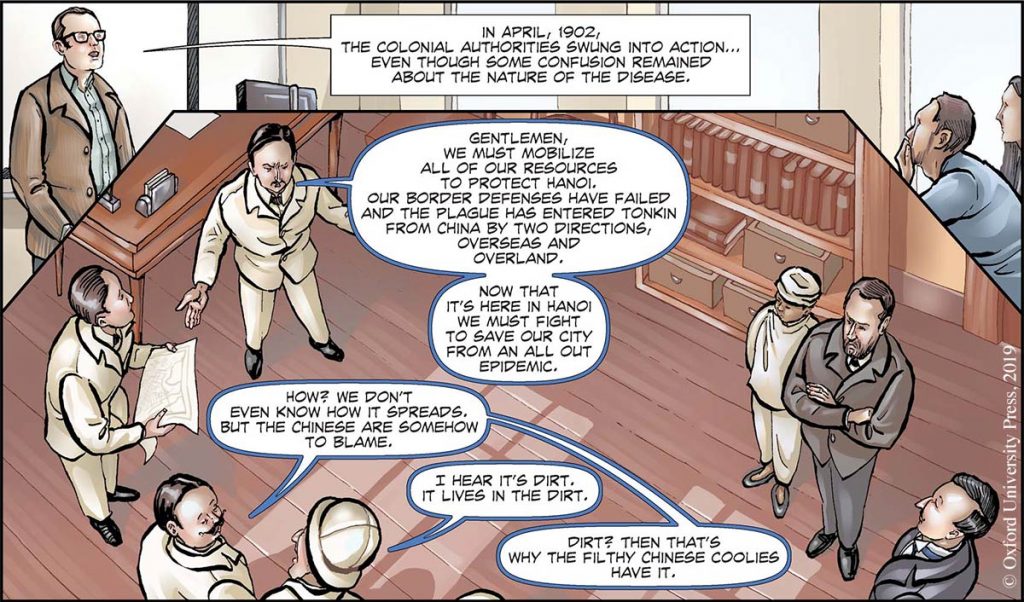

The link between pandemics and racism is almost as old as disease itself, with colonial attitudes fast pinning the cause of disease on the poor hygiene, bad sanitation and dodgy medical practices of “backward natives.” Privileged classes have long justified segregation and other xenophobic policies in these terms. Race should have little to do with disease, but it is always there. The white-man was accused of causing Rinderpest in 19th century South Africa. The Jews were blamed for typhus in Nazi Germany. The Chinese, Japanese and Mexicans were blamed for small pox outbreaks in 20th century America. While diseases come and go over time, prejudice never does, preferring to stay put and use epidemics to fan its flames.

In late 19th-century Hanoi, the French ruling class responded to a bubonic plague outbreak by blaming the Vietnamese and Chinese, citing a lack of “modernity.” Instead of properly dealing with the disease, the colonists outsourced plague relief efforts to Vietnamese rat-catchers, who put their own lives at risk. However, it soon became clear that the true purveyors of disease were not the Vietnamese, but the French themselves.

The coronavirus means that while virtually everyone remains cautious about airborne germs, many must now also be wary of violence just because of where they are from or the color of their skin.

Considered a cornerstone of colonial modernity, the French-designed sewer system doubled as an agreeable breeding grounds for thousands of rats and the resulting disease. The capital city witnessed more than 200 deaths from 1906 to 1908, as local newspapers called it an “petite épidémie.” The plague only lessened after French officials began finally caring about the wellbeing of the native Vietnamese through public health regulations and monitoring for the disease.

The coronavirus means that while virtually everyone remains cautious about airborne germs, many must now also be wary of violence just because of where they are from or the color of their skin. On March 2, one of the earliest cases of coronavirus-related hate took place in the U.K. Jonathan Mok, a 23-year old Singaporean student in London was beaten to the ground by several attackers. Before drawing blood with a punch to Mok’s nose, one of the attackers shouted: “I don’t want your coronavirus in my country.”

In the aftermath, Mok took to Facebook to voice his disgust. “Racism is not stupidity – racism is hate. Racists constantly find excuses to expound their hatred – and in this current backdrop of the coronavirus, they’ve found yet another excuse.”

Racist sentiment surrounding the virus has also appeared in the art world. An Nguyen, a Vietnamese art curator, was uninvited to an art fair in the U.K. Raquelle Azan, a New York-based art dealer, explained the reasoning in an email to Nguyen: “The coronavirus is causing much anxiety everywhere, and fairly or not, Asians are being seen as carriers of the virus. Your presence on the stand would unfortunately create hesitation on the part of the audience to enter the exhibition space.” The exhibit should have brought Western audiences closer to Vietnamese culture, instead a Vietnamese voice was erased in wake of the pandemic.

“It is so pathetic. In a country where people don’t accept you and they criticize, this is just a bitter humiliation.”

U.S. President Donald Trump dubs the disease the “Chinese Virus” despite the World Health Organization already classifying it as COVID-19. The WHO warned Trump about his dangerous rhetoric, chastising him for putting Asians across the globe at risk. In an effort to decrease racial tension and solely focus on the disease, WHO’s preferred, scientific name for the virus does not stigmatize any particular group. Unfortunately, Trump’s insistence on racializing the virus upends those efforts.

When asked if he thought his rhetoric put Asian-Americans at risk, Trump brushed it off, saying, “No not all. I think they would agree 100%. It comes from China.” Many Asian-Americans have since experienced hate crimes, including a family of three getting stabbed in a Texas supermarket by a 19-year-old. Authorities concluded that teenage attacker committed the crime because “he thought the family was Chinese, and infecting people with coronavirus.” A recent FBI report indicates a surge in anti-Asian attacks, stemming from belief that the virus is caused by Asians. Panicked racists, emboldened by the president, only add to the chaos of the pandemic.

With the virus starting in Wuhan, China, it comes as no surprise that the Chinese have come in for a huge amount of racism. Many initial reports of the virus coincided with the Lunar New Year, a popular travel time for the Chinese. Throughout Southeast Asia, hotels and restaurants hung signs prohibiting Chinese patrons. Malaysians petitioned for the banning of Chinese travelers, believing “the new virus is widely spread throughout the world because of [their] unhygienic lifestyle.” Vietnam’s often toxic online community began spewing outlandish conspiracy theories, claiming China intended to poison the Vietnamese by exporting spoiled food.

With so much racism being thrown China’s way, you might assume they would be anxious to not engage in racism themselves. It would seem not. Earlier this month, many Africans living in Guangzhou were unceremoniously evicted from their apartments and hotels as they were wrongfully seen as carriers of the virus. A branch of McDonalds in the Chinese southern city even banned black diners. With no one wanting to take the newly evicted, some resorted to sleeping on the streets. Nigerian expat Chris Leslie vented his frustration to CNN, “It is so pathetic. In a country where people don’t accept you and they criticize, this is just a bitter humiliation.” Many fear these racist responses will uproot the African community in Guangzhou forever.

The racism has not just been thrown around at Asians and Africans either. As Europe and the United States have become new epicenters of the disease, white expats in foreign countries have also faced prejudice. In Thailand, Health Minister Anutin Charnvirakul made discriminatory remarks against Europeans, tweeting they are “dirty” and “never shower.” Despite the government’s attempts to protect foreigners from discrimination, some expats in Vietnam say they have been denied taxis and other services with two words: no foreigners. Some expats in Vietnam have become anxious. “Given that our American government messed up… do you think that the Vietnamese people will be afraid of interacting with Americans visiting Hanoi?” an American expat wrote on a Hanoi expat forum. As Vietnam is usually so welcoming to foreigners, witnessing these legitimate concerns is jarring.

With the entire world suffering, prejudice is not the solution. Hate crimes, biased authorities and scapegoating conspiracies do nothing to stop infection.

As the statistics start to trickle in, the grim figures reveal coronavirus is ravaging the communities of immigrants and people of color. Why? Because generations-old racist systems have left these people vulnerable in the face of a pandemic. The main culprits are denser housing in poorer neighborhoods, income inequality, and a lengthening social divide between minorities and the state. For instance, African-Americans now worry they will be profiled as criminals for wearing CDC-advised facemasks, after two black men in Illinois were followed by a police officer when shopping for essential supplies. In a similar instance, a black doctor in Miami was handcuffed by an officer when trying to deliver tents to the homeless. In a recent op-ed published by the Boston Globe, writer Aaron Thomas lamented the added pressures of surviving a pandemic as an African-American male: “For me, the fear of being mistaken for an armed robber or assailant is greater than the fear of contracting Covid-19… We are living in an America where history dictates that, even in the most absurd times, hatred and bigotry continue to reign.”

With the entire world suffering, prejudice is not the solution. Hate crimes, biased authorities and scapegoating conspiracies do nothing to stop infection. Meanwhile, the international medical community is racing to find a cure. Once a vaccine is created, there will be a need for an unprecedented amount of international collaboration to effectively manufacture and deliver the vaccinations. Xenophobic thinking will only exacerbate this global crisis, as it has already.

It is worth noting that major world powers displaying nationalist ideals were significantly impacted by the virus. As the virus swept through Europe, government officials in the U.K. were more concerned with finalizing Brexit, a movement partly fueled by racist dog-whistling and Islamophobic tropes. Indeed, the Brexit-machismo of the British government was so intense that on multiple occasions it refused to join an EU scheme that would have allowed it to bulk-buy personal protective equipment for its medical staff. It is now short of such equipment. In the United States, Trump is using this opportunity to double-down on nativist policies on the U.S.-Mexican border. While closing the borders is a sensible short-term solution to quell the virus, many fear Trump will continue to lock down borders after the pandemic. Many undocumented immigrants, whose agricultural work is still deemed essential by employers, are now refusing to get tested for the disease due to fears of deportation. It seems xenophobia all-too-often trumps health when it comes to sensible policy-making.

Meanwhile, China’s nationalist fervor over the “Taiwan issue” nullifies the island-nation’s positive preventive steps. With the WHO’s failure to recognize Taiwan as a nation-state, the island was not invited to an emergency meeting between more powerful nations, despite demonstrating life saving measures that would have helped the world. Again a powerful nation, and a powerful institution, has made matters worse by placing jingoism ahead of health.

History has proven that racism, while a sociological symptom in the response to pandemics, is never a suitable cure for them. As the coronavirus ravages the planet, it is important to not recycle history’s racist responses. Such ignorance will only stoke unnecessary hatred and lengthen the virus’s grip on the world.

For perhaps the first time in modern human history, every individual, regardless of race, is affected by the same problem. Any blame leveled at a people or nation is not only foolish, but a waste of time and energy better spent on fighting the virus. This is not the moment for biases or accusations. This is the time for empathy. Once the lockdowns have ended and children restart schools, let us return to one another with a new understanding: that in the face of crisis, all must be protected, or none will.

You may like

-

16 new coronavirus cases confirmed in Vietnam

-

Vietnam to operate 13 repatriation flights next month

-

Update: Hanoi students not returning to school on March 2

-

Hanoi woman re-tests positive for Covid-19

-

Hanoi hopes for students to return to school in March

-

9 new coronavirus cases confirmed in Vietnam

-

15 new coronavirus cases confirmed in Vietnam