Art & Culture

[Book Review] Prostitution and Venereal Disease in Colonial Hanoi

Vietnam’s greatest 20th century writer takes a look at Hanoi’s colonial-era flesh trade

Published

6 years agoon

Maybe the client has already paid his money,

But only have sex the proper way!

As soon as it is over,

Soap and iodine on the places that it flowed

[Excerpt: “The Ballad of Eros”- Early 20th Century Vietnamese sexual-health poem]

In 1930s Hanoi, prostitution was big news, employing around 5,000 of the city’s population of 180,000—likely over 5% of women were prostitutes—and if you include the suburbs, the numbers were significantly higher. Add to this the various other people who were employed off the back of this most ancient of trades (madams, pimps, hoteliers, rickshaw-pullers, etc.), it was one of the key drivers of the city’s economy.

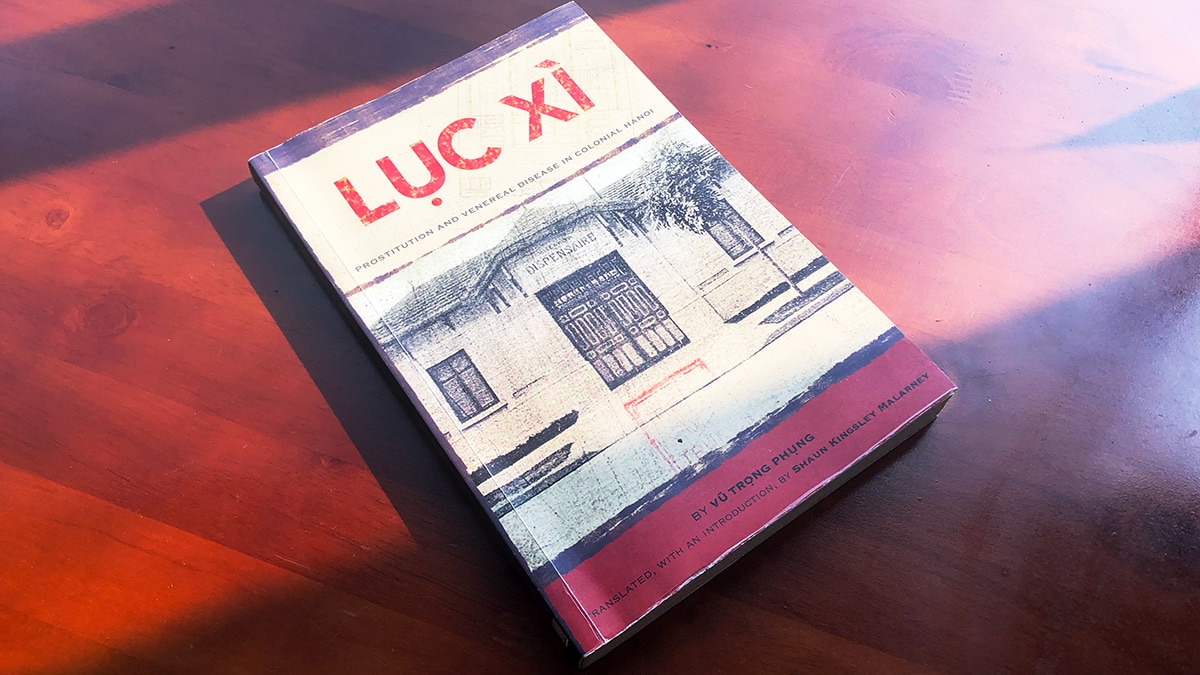

In “Prostitution and Venereal Disease in Colonial Hanoi” (Luc Xi), much lauded Vietnamese novelist and journalist Vu Trong Phung (1912-1939) investigates the city’s flesh trade with a view to understanding what is causing it and what can be done about it (if anything at all).

In an act of journalist reportage (a style popular throughout the 1930s), Vu Trong Phung speaks with nurses, prostitutes, doctors, healthcare workers and government officials to gain an understanding of the problem. As the book’s Vietnamese name suggests, the writer primarily centers his research around the luc xi, a sort of medical dispensary, serving as something between an inpatient STD clinic and a prison, depending on your outlook. The work was originally published in 11 installments in the newspaper Tuong Lai (Future). and perhaps because of this lacks a certain cohesion, but it is nevertheless a fascinating document, which gives an eye-opening, occasionally jaw-dropping, first-hand insight into a very specific of life in late-colonial Hanoi.

Translator Shaun Kingsley Malarney includes an excellent and scholarly 40-page introduction, which gives much needed context, allowing you to pick up on a rich variety of details that would otherwise be missed. One such detail is Malarney’s discussion of what luc xi literally means. He is not quite sure but, concurring with Phung, says the best explanation is that a doctor who enjoyed using English phrases would point at prostitutes’ vaginas and say “look see!” in a vignette that presumably left the poor women unamused.

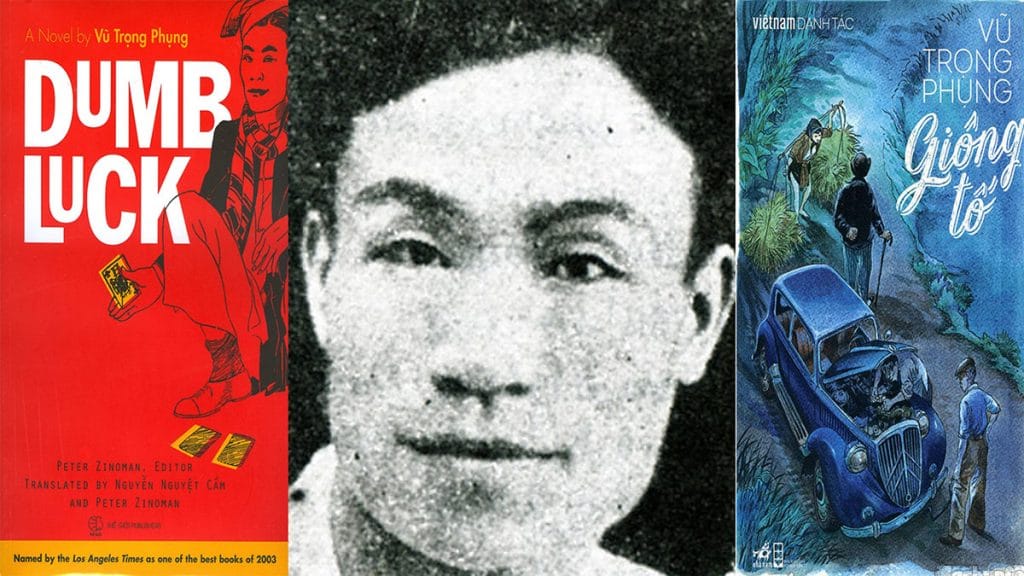

Vu Trong Phung sits among the very front-row of Vietnamese writers and his body of work has been described as” the single most remarkable individual achievement in modern Vietnamese literature” His novels have echoes of Charles Dickens and his non-fiction of George Orwell—like Orwell his surveys of the poor and downtrodden are a curious mix of disgust and sympathy. More than 100 years since his birth, he is still taught in Vietnamese schools today.

Instead of having to go through the motions and have sex, the prostitutes are happy that they are just asked to chat about their lives and smoke opium.

“Luc Xi” is not for the fainthearted, and readers would be well-advised to approach it with a doctor’s healthy respect for the body, as well as expectation of the attention-grabbing prose of a journalist trying to shock and grab his readers. One minute things appear quite straightforward, boring even, and the next there are graphic explanations of how French soldier’s “reluctantly” insisted on having anal sex with their prostitutes in the mistaken belief that this would keep them clear of STDs–a belief which led to up to 40% of prostitutes at the time having anal venereal diseases.

The detailed descriptions of how far the prostitutes would go to fake their own sexual health will also be too much for some: “If in spite of these methods the secretions still turn the handkerchief-tampon yellow, very sick women have recourse to final method; it consists of inserting into the vagina noncoalugated pig’s blood, which can be ordered from a butcher to simulate mensuration.”

Despite Vu Trong Phung being quite the reformist and ahead of his time, the book was nevertheless written in 1937 and readers may, quite justifiably, have difficulty with some of the more outdated attitudes expressed in it. Masturbation is seen to “weaken the mental faculties.” Vietnamese women who live with westerners do so “only because of the money.” Mixed-race people are “the bad points of both races brought together as one.” The sexism can be brutal too: “If some women in the cities are civilized and progressive, in contrast, 99 percent of the other women are still inferior in every way to men.”

Phung also often seems to embrace what today would probably be seen as a boomer-mentality, and at times you almost expect him his to start sentences with “The kids of today…” or “Things are not what they used to be…” as he laments the decline of religion, or father’s not being able to properly discipline their daughter’s any longer; this is all made extra confounding by the fact that Phung would only have been 25 when he wrote the book.

But a book will always be of its time, and despite some of its faults it does serves as a valuable window into some of the thoughts and feelings of the era, as with the frequent mistrust Phung shown for being a newspaper writer (some things never change). “You’re all journalists? So for which ‘rags’? Go on in, and then go write some more garbage!”

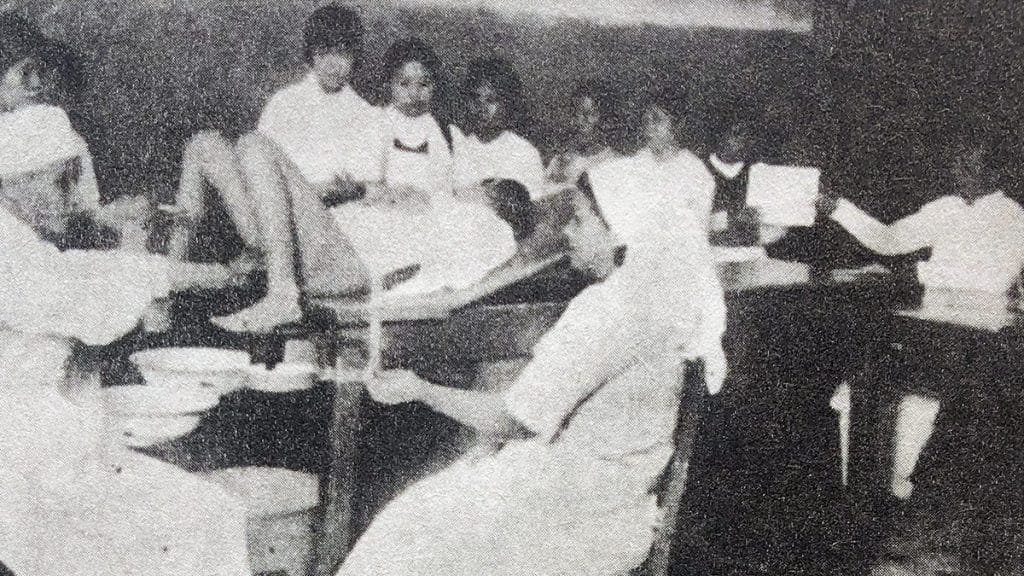

Girls sent to the dispensary were virtually all illiterate, and one of the ways they learned sensible sexual health practices was through learning the words of a public health poem called “The Ballad of Eros.”

As he is a journalist, a certain number of readers would, no doubt, think that Phung decided to report on prostitution out of pure prurience and or because he wanted to sample the goods, and he is often at pains to point out this is not the case: “I will not ‘investigate’ all of the seedy hotels, the devil’s dens, the out-of-the-way places. It is not necessary to grease the palms of the boys at the seedy hotels or the nighttime rickshaws drivers, just as it is not necessary to work one’s way into the hearts of the licensed prostitutes… I will conduct an investigation only from the written works that discuss the problem.”

Phung is doing himself a bit of a disservice here—he conducts plenty of interviews—but overall his reportage suffers from this approach. He only actually talks to two prostitutes at length, and he may have been better off being a bit more gonzo in his reporting. The meeting with the two prostitutes covers some of the best exchanges in the book, as when one of the interviewees demand’s to get high (“let me smoke some opium, or it’ll be too fucking boring”). Phung immediately orders some (and partakes). Instead of having to go through the motions and have sex, the prostitutes are happy that they are just asked to chat about their lives and smoke opium. “Damn! If only we had clients like every night; what a life! Working in a brothel would be great!”

It is notable quite how enlightened the approaches were to prostitution back then. It was widely seen as a public health problem as much as moral one–venereal disease was virulent at the time—and responses to it seem to have been a choice between if prostitutes should just be left alone to do what they like, or to what extent they should be regulated. At the period of writing about 10 percent of the city’s papers prostitutes had official papers, which meant they could legally work in licensed brothels provided they had a regular health check up at the luc xi.

Now this harm-reduction policy does not seem to have been very effective but this is much to do with corruption, commitment and the institutional resolve towards supporting it, rather than it not working as an idea per se.

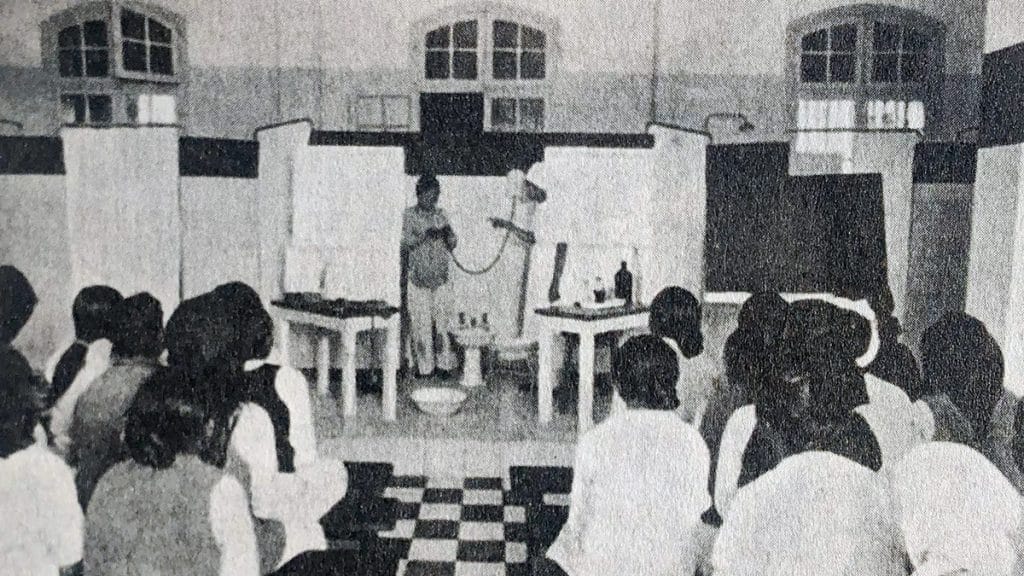

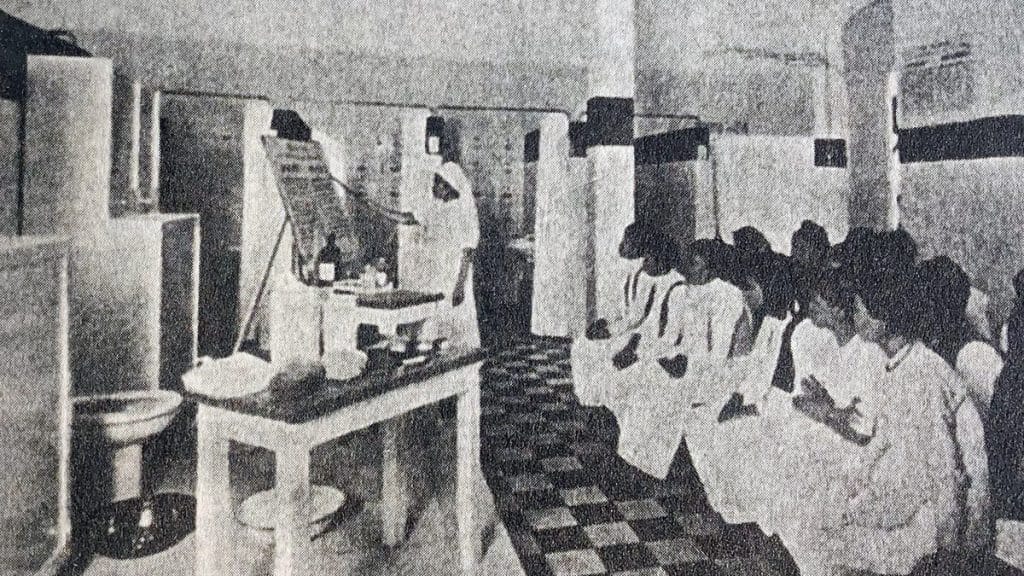

Phung is very excited about gaining access to the dispensary as it was largely off limits to all but a few medical workers and the prostitutes themselves. The clinic itself is routine, regimented and boring for the girls (no alcohol, opium, or gambling allowed) and there are some cruel punishment incurred for wrongful behavior, but it largely seems a responsible institution, with a sensible approach to health, albeit constrained by the limited public health knowledge available at the time

Girls sent to the dispensary were virtually all illiterate and one of the ways they learned sensible sexual health practices was through learning the words of a public health poem called “The Ballad of Eros.” Girls were not able to leave the dispensary until they had memorized it in full. It is too long for a complete version here but a few random versus should suffice:

Life has eating, drinking, fun and laugher.

Carousing, betel, smoking, gambling; isn’t that enough?

Venereal diseases are terrible; learn how to prevent them!

Men, they’re terrible, such monsters!

They pour their amorous venom into us,

We’ll give it to others and surely cause greater harm.

If you see any one with a forehead full of red spots

…

You must stay far away from him;

Don’t let him slowly get near you.

He is dangerous like a tiger!

Take good care! Don’t be reckless with your body

Though my no means a comprehensive study off its subject matter, “Lux Xi” gives a good over view of prostitution in colonial Hanoi and the cafes, seedy hotel, dance halls, and pimps that were sustained by it. Phung is by turns scathing and satirical, sarcastic and serious. The book serves as a fantastic primary source for investigating colonial Hanoi and the attitudes towards the “Europeanization” that came with it: a brilliant and curious read.

Photographs not credited are the courtesy of Manhhai.

You may like

-

Red Sunday blood donation campaign opens in Hanoi

-

Hanoi to pilot air quality monitoring system

-

Update: Hanoi students not returning to school on March 2

-

Hanoi woman re-tests positive for Covid-19

-

9 new coronavirus cases confirmed in Vietnam

-

15 new coronavirus cases confirmed in Vietnam

-

18 new coronavirus cases confirmed in Vietnam