Art & Culture

How to eat like a Vietnamese

If you make a mistake all will be forgiven, but there is no harm in knowing the dos and don’ts of the Vietnamese dinner table

If you make a mistake all will be forgiven, but there is no harm in knowing the dos and don’ts of the Vietnamese dinner table

Published

5 years agoon

By

Linh Nguyen

Besides your classic must-try Hanoi eateries, nothing captures the essence of Vietnam quite like a local family dinner. Like many of its neighboring Asian countries, Vietnam’s culture is a communal one, and our primary love language is food.

Mom’s plate of sliced-fruit during my late night studies speak for her worries, and me asking “have you eaten yet?” is how I express mine. Food and its surrounding etiquette is multi-layered. Embedded in every traditional Vietnamese meal is a world of custom and culture, which those around the table (or sitting on the floor!) must follow. We have a saying in Vietnam: “ăn trông nồi, ngồi trông hướng” (keep an eye on the pot while eating, watch the direction where you are sitting)– advice to mind your manners while eating, but also in life.

These complex and often unspoken rules can be confusing for first-timers. So, let’s take a walk through what a typical Viet dinner might entail.

Those with a sharp ear will notice that the Vietnamese almost always say they are having “a meal of rice,” whether it’s breakfast, lunch or dinner. Though rice doesn’t have to be present, obviously. Just last week, I told my sister to come out and “eat rice.” It was spaghetti night. Rice has always been the staple in Vietnam, so much so that it has become a habitual phrase. Whether it’s good ol’ mac-n-cheese or Chinese wontons, when placed on a local dining table, the dish magically transforms and we are eating “a meal of rice.”

Beside the beloved white grain, a typical Viet meal consists of a vegetable dish, a protein dish, and canh, a brothy soup generally to be poured over the, yes, rice. More often than not, a quintessential bowl of fish sauce is presented right in the center of the table for all to share.

Once seated, diners must ritually invite each other to dig in, or mời cơm. It’s the rough equivalent of the French Bon Appétit, or the Japanese Itadakimasu. It is usually a one-way street: the young saying it to the old, and it must be said first to the oldest person at the table, usually the grandparents or, perhaps, dad– then you move down the hierarchy. Baby brother eventually being allowed to tuck in too.

Everyone can eat after the oldest person takes the first bite. And yes, it’s a privilege that comes exclusively with senior status, a reflection of how filial piety is ingrained in our world, a large part due to the Confucian ethics introduced to feudal Vietnam during China’s occupation, over a millennium ago.

Mời cơm is still a common scene in every Northern Vietnamese household. As a Viet gal, I’ve had my fair share of thunderous look sent my way when I (as I child I hasten to add) forgot to ‘mời cơm’ my family. Let’s say there were a few tear-filled meals here and there.

“One time, I saw this boy wolfing food as if there was a storm chasing his back, taking the best pieces for himself. That uncultured punk! His parents should have taught him better.”

Traditionally extended families would all reside under one roof: grandparents, in-laws, parents, children, all sharing the same meal. How well a child pays respects to one’s elders was, and is, used to judge a parent’s’ child-rearing skills. Expect disapproval or even sneering backhanded comments if you do not get this right.

“Know that there’s a structure to everything, we are a family that follows (Confucius) values and teachings. When I was young, I always give the biggest, most delicious dishes to my parents and my younger sister,” Dan, now 85, reminisces. “One time, I saw this boy wolfing food as if there was a storm chasing his back, taking the best pieces for himself. That uncultured punk! His parents should have taught him better.”

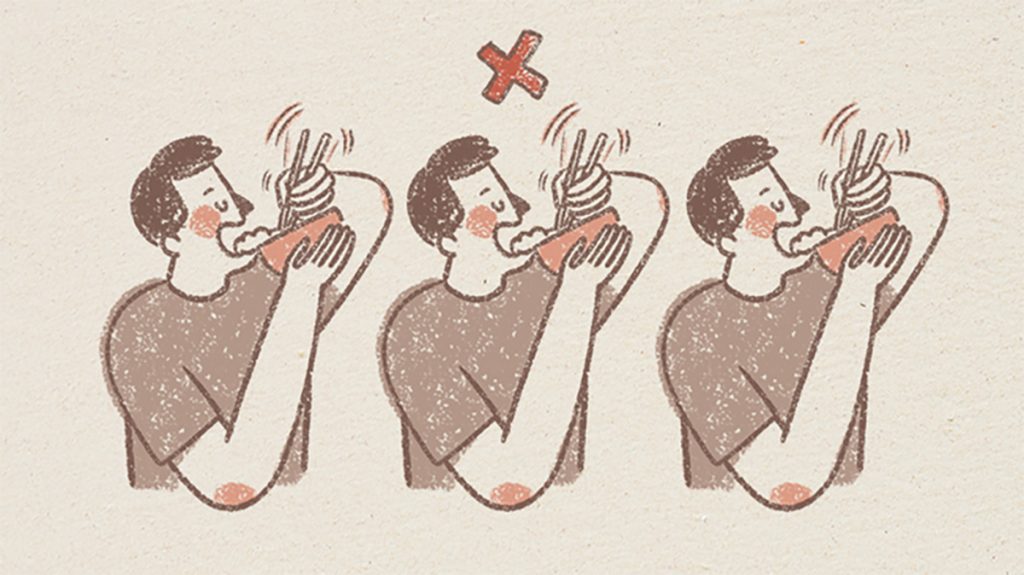

Spiritual people the Viets are. Here, the world of the dead and the living often intertwine, and us earth-roamers are careful not to upset potential evil beings, which is reflected in the way we handle chopsticks, our holy grail when eating pretty much anything and everything. Slackers, like me, have even known to use them to pick up Lays chips (it saves time washing hands).

Young-uns who don’t know better, and tap their chopsticks feverishly onto the side of a bowl are quickly hushed by their mothers. This is a big no-no: the tapping noise is believed to act as a siren summoning aimless souls into your home, including ones of an ominous nature.

A pair of chopsticks should never be jammed into the rice vertically, as such placement is reserved purely in a ceremony for the dead, as with incense sticks at a temple. Scooping rice into a bowl has its own rituals too–it is also believed to relate to worshipping ancestors–two spoons is for humans, three is for the dog. Thus, no matter no little or how much you eat, two scoops is the way to go.

Looking around the table, if the day’s menu includes a fish in its entirety, then no matter what, do not flip the fish! This is a taboo act as it represents a flipping of a boat at sea. Such superstitions abound in a country with such a large coastline and so many fishermen.

The etiquette may seem a bore to some. “Why don’t we just get on and eat?” I hear you say. But these customs are passed down from generation to generation. It’s just the way thing are.

“It started as something forced upon me, who would wanna get scolded? I followed these rules simply because that’s how I was brought up!” says Be, 23, the granddaughter of Dan. “But now, besides from the nonsense, the superstitious rules here and there, I think I’ll raise my future children to have the basic etiquette. They show my roots, what it means to pay respect and express love to the people we care about.”

“If I were to end up with a non-Vietnamese person, I would totally teach them about these rules. You marry me, you marry my culture. It’s a package deal.”

Don’t eat every last bite! As the meal comes to an end, you may notice a small bit of food left in each dish. That’s “the bite of shame.” Whoever dares consume this final piece of food is dubbed ‘shameless,’ implying they are greedy and even impolite. But fear not, there’s an element of jest to this. Eating all your food is the biggest compliment you can pay to any cook, no matter the culture.

At end of every meal, assorted fruits such as apple, guava, watermelon are brought out, a far cry from the fantastic yet often overly-sweet, calories-dense desserts you often find at the western table. This is no surprise, since Vietnam has largely always been known for its healthy diet.

As a guest, this is your time to shine! Vietnamese are hospitable peeps who love it when you show the same spirit. No need for fancy gifts– a simple basket of fruit serves as a wonderful gift if you are invited to a family dinner.

Does a foreigner even need to know these arcane rules? Truth be told, you will be forgiven for not knowing, but effort is always appreciated. And if you are really going to live here long-term, you probably ought to. At least Be thinks so:

“If I were to end up with a non-Vietnamese person, I would totally teach them about these rules. You marry me, you marry my culture. It’s a package deal,” she says.

Ultimately, the formality of Vietnamese dining will vary from one family to another, and the younger generations may wean off some of the more offbeat etiquette in the future– for better or worse. Regardless, such rules offer an intriguing lens into the inner world of Vietnam. And don’t they play a role as a gatekeeper, protecting the country’s idiosyncrasies? I, for one, think they do. Now off you go. Go eat rice!