Art & Culture

The names behind the Hanoi Streets: Nam Cao

A writer whose bitter life was often mirrored those of his own downtrodden characters desperately trying to survive

A writer whose bitter life was often mirrored those of his own downtrodden characters desperately trying to survive

Published

4 years agoon

By

Ha Doan

Tucked in the middle of Tran Huy Lieu and Nui Truc street, Nam Cao street is easily missed when passing through Ba Dinh District, while others mistake it with the busy, interconnecting road Van Cao. The street is quiet and only runs about 300 meters. However, despite its seeming insignificance, it is named after one of Vietnam’s great writers, a leading figure in building a new realist literary genre.

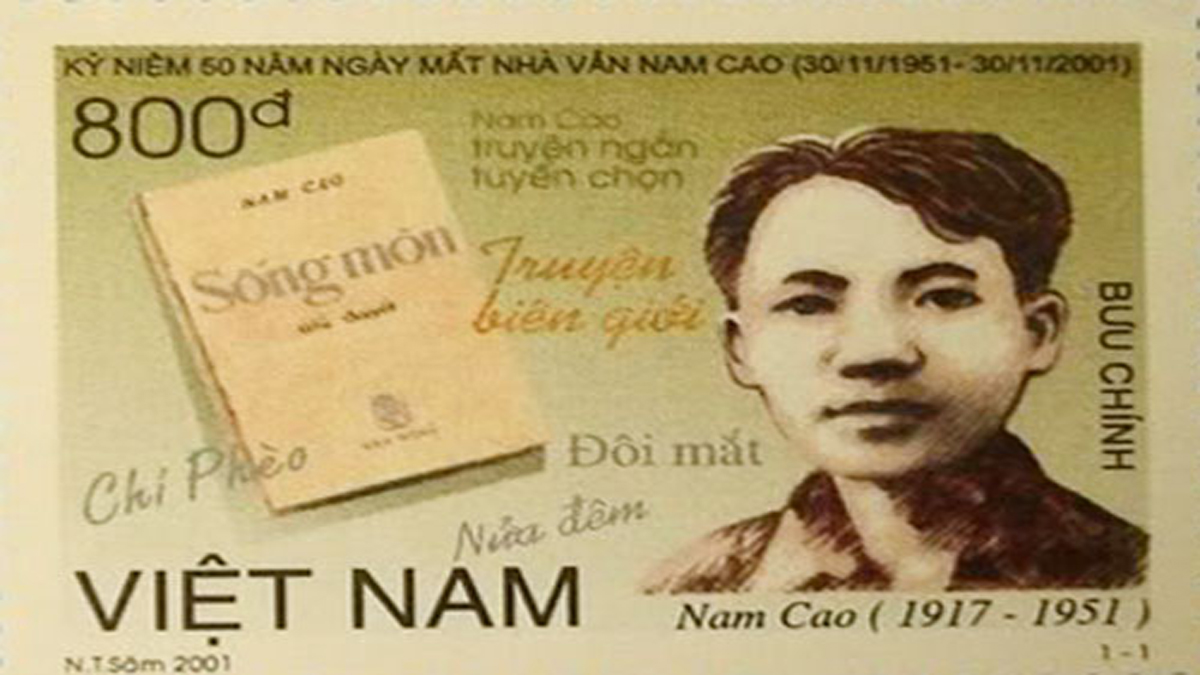

Named at birth as Tran Huu Tri, Nam Cao (1917-1951) was born into a typical peasant family in Ha Nam Province, northern Vietnam, spending his childhood in a land plagued by poor soil, drought and few crops. His family and later Nam himself, struggled through life, but as the first in his family to receive a formal education he was able to deploy this humble upbringing to inspire much of his work in his early and most recognized pieces, including “Chi Pheo” (1941), “Old Man Hac” (1943), and “Corroded Life” (1944). His work has even had an impact on the Vietnamese language itself, the titular character Chi Pheo now used as a catch-all term to describe a certain genre of feckless, idle (often drunken) person, always on the look out to make a quick buck, whatever it takes. We have all met a few.

After going through the French secondary school system and receiving the Thanh Chung diploma, Nam Cao moved to Saigon with the hope of going abroad to continue his studies, but the poor health that was to haunt his life prevented him, and after a few jobless years he took a teaching position in a private school in Hanoi in 1938 instead.

After a brief flirtation with romantic writing he turned to a more realist style, with his short story “Trang Sang” considered a turning point. In it he made his transformation clear, famously writing: “The arts are not deceptive like bright moonlight, and nor should they be. The arts are only the mourning echoes of those suffering and oppressed.”

His work focused on the life of farmers and the lower middle class before the August revolution. Using the forensic skills of an investigative reporter, he captured the essence of a period defined by hustle and improvisation during rampant famine, as well as a spiritual longing to escape the life of what he called people “dying in vain, dying without actually living.”

He is outcast from society and, perhaps predictably, he futilely attempts to keep his dignity through suicide, his dying words: “I just want to be a good man. Why can’t I be a good man?”

Much like his own characters, Nam Cao struggled financially, and lived his life every inch the struggling writer until, perhaps for the first time ever, he struck luck with the publication of “Chi Pheo.” It is said that upon receiving the story, the Doi Moi publishing house threw it on the slush pile and then the trash bin where it was chanced upon by the respected novelist and journalist Vu Bang, a sub-editor at the time, who pushed for printing the story and remained a strong advocate of Nam Cao his entire life.

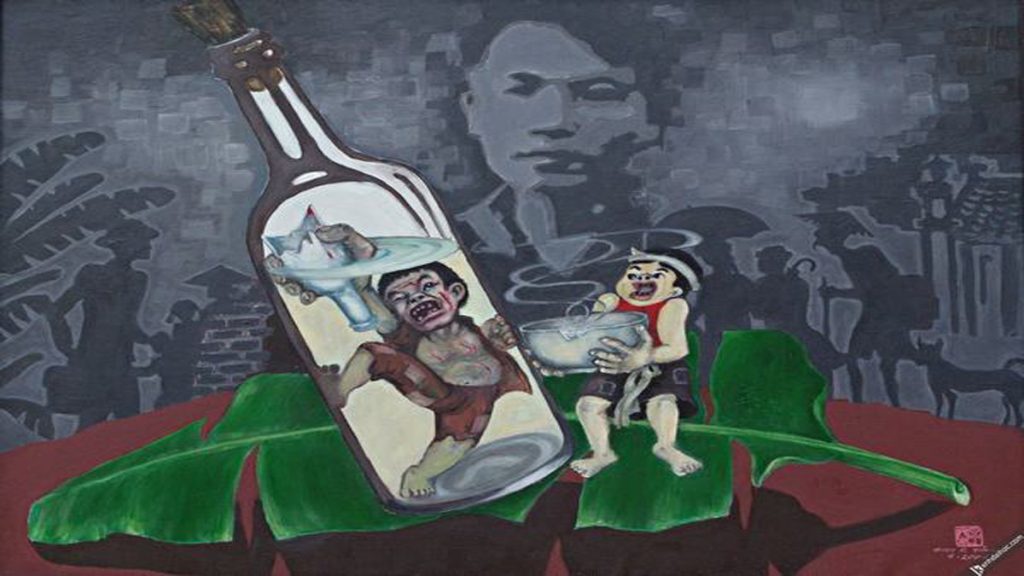

Named after the protagonist, “Chi Pheo” narrates the tale of an abandoned child who is later enslaved by a tyrant landlord and unjustly imprisoned by him. The horror of such conditions sees Chi Pheo descend from a kindly, compassionate young man into a vindictive bully, cursing, quarrelling and causing scenes through regular drunkenness. He is outcast from society and, perhaps predictably, he futilely attempts to keep his dignity through suicide, his dying words. “I just want to be a good man. Why can’t I be a good man?”

The extended metaphor for how a corrupt colonial-feudal society abused and oppressed the most vulnerable was an instant success, briefly making a name for the, until then, unknown Nam Cao. His work continued to reflect his life and the difficulties he endured, making it deeply empathetic, poignant and dark, yet still hoping to illuminate the beauty of the downtrodden whose lives were invariably obscured by the outward roughness of living an all-too-tough existence.

“Literature is not about crafting or modelling according to any formula. Literature only endures those really digging deep down and finding out what has not been discovered, or creating what has not even existed,”

His work can be contrasted with other leftist writers of the era who were perhaps more biting, satirical and humorous. While Red Haired Xuan, the protagonist of Vu Trong Phong”s Dumb Luck relentlessly falls upwards despite his poverty in the midst of the fag-end of colonial Vietnam, Chi Pheo has no such luck–his destiny the reverse, society failing him at every turn.

Despite “Chi Pheo” being widely read, life was harsh on Nam Cao, and he seemed to age quickly in spite of his youth.

“He was only 23 or 24 at that time, but I would not doubt it if I was told he was 35 or 36,” Vu Bang said of their first meeting. “Measured in every of his own movements, he usually tucked his hair behind his ears. Poor him… I hope no one thinks this is because he fancied himself a hippy, as he simply couldn’t afford a proper haircut.”

Like many a writer before and after him, Nam Cao never received the recognition he deserved during his lifetime. “Of Vietnamese literature during anti-French resistance period, Nguyen Huy Tuong takes the lead, second comes To Huu and Kim Lan, while Nam Cao is the slowest,” he once wrote of himself. Some pity him for drawing little confidence and satisfaction from his work, others simply think he had high standards.

“Literature is not about crafting or modelling according to any formula. Literature only endures those really digging deep down and finding out what has not been discovered, or creating what has not even existed,” he wrote of his writing philosophy.

While returning home after completing a mission for the Cultural Association for National Liberation, he was ambushed and killed by a group of French commandos in Ninh Binh Province. “The death of a man as exceptional as Nam Cao is a great loss to our literary field,” Vu Bang said in his grief. Today his work endures, with high-schoolers across the nation expected to study his work in considerable depth.

His talents only garnered significant public attention after his death, with many of his short stories published posthumously after being kept intact and brought into the daylight by his close friend To Hoai. They received huge praise, some even making their ways to movie adaptations, such as the classic “Vu Dai Village in the Past.” Many of the characters and places in his work have become iconic, or serve as tourist attractions, such as Vu Dai Village, which was modelled after his hometown of Dai Hoang.

Nearly 50 years after his death, Nam Cao’s remains were discovered and returned to his homeland, now not as an obscure writer but as a literary giant: perhaps something to ponder, should you walk down Hanoi’s blink-and-you-will-miss-it Nam Cao Street.

“The names behind the Hanoi streets” unveils the great historical provenance behind our favourite streets to get a bia hoi fix, bun cha, or anything Hanoi-wise for that matter.

The names behind the Hanoi Streets: An Duong Vuong

[Days gone by] Opium: How the ‘Brown Fairy’ swept across colonial Vietnam

The names behind the Hanoi streets: Nguyen Trai

[Film Review] The Housemaid

[Film Review] Hanoi: Winter of 1946

Badass women of Vietnamese history: the sensual poet

The names behind the Hanoi Streets: Tran Hung Dao